Touch: The Journal of Healing

Covet

By Monique Hayes

You’re sacred like a stain glass window. I look at your enlarged freckles, the curves under your cotton blouse, and the lines that criss-cross at the edges of your eyes. You’re all youth, with color in your cheeks. I used to believe that if you breathed hard enough, there’d be a heartbeat that would break you in half. I think we both miss when it wasn’t a crime to be shapely in school.

I enter your walled Walden Pond once a week. They teach you how to grocery shop, plan meals, and that it’s okay to cry and converse, these monthly moms that do so much while I do just enough. Like Thoreau, you perform quiet crafts in your immaculate room. Today, you give value to little women, winged and mythological, in your natty notebook. You worry about the length of legs, the tightness of torsos, and the stoutness of shoulders. I watch you care. It is angled anger, insecurity driving ink in voluminous silence.

But it’s better here than there. There, you were in the waves of blankets and hospital sheets. Your fingers were as slender as eyebrows. You called the IV tube a fat, food-filled needle and said it was as annoying as the participatory ribbons they hand out after science fairs. Whenever you went to consultations, I made your bed, listening to the light crackle of tucked corners after I finished. Someone remade it after I left. Whenever you slept, I watched the tiny particles travel from the bag to your thin arm. I still hate to admit that I coveted that closeness, having the need to give you nourishment. Would you ever take it?

Nobody calls Tinkerbell “Thunder Thighs.” Is she the first female you saw after me? I don’t have the courage to ask, letting my suspicions sink in as you concentrate on your creatures. I imagine you inspecting your reflection in the dining room silverware. I imagine you checking calories in the aisles of the small town Safeway. I imagine your skinny fairies spinning pirouettes on top of a swimming pool where we each wear two-piece bathing suits. The third one is the richest to me because I know how far it reaches.

“Did you eat breakfast this morning?” I ask.

“Yes,” you say. “With the warden.”

You scribble for awhile and then draw pointed ears. You have my ears, the Patterson peak that rises to the edge of our foreheads, and the peak we both pierced on a whim during a trip to Wildwood. With our pierced ears, we could hear the rides down by the pier— the Great White, the Maelstrom, the Sea Serpent. We were headed for more dangerous territory, a T-shirt shop. You collected five sizes and ducked into a stall. I’m pretty sure you didn’t read the price tags. I asked if you were alright. You replied with a barely there “I’ll be out soon.” The “soon” went on for several minutes, until an employee asked the same question. There was a small cry and I went in to check. The shirts were strewn on the floor and you were shaking, hugging yourself on a stool near a mirror. You said that you went up a size, not to touch you. We left without a purchase and without a word between us. You were twelve and terrified. I was thirty-five and an academic. I know that’s no excuse.

“During the Renaissance, people liked women with fuller bodies,” I say, nodding to your notebook.

“Then, the Renaissance was full of heifers,” you say.

I go to shape your pillow on the bed you’ve had for sixty days thus far. The comforter is soft and cold. Your handy, homemaker dad knitted it before we brought you here. He called you and the comforter his greatest achievements. My achievements are things you don’t care to understand—book reviews in bound periodicals, annotated bibliographies with works on Spenserian stanzas, and tracing the history of performances at the Globe Theater. We can’t trace some of our similarities in our bodies anymore. You’ve thrown off certain genetic guarantees by making changes, by keeping a close eye on yourself. What stings is that you’re satisfied with it, with not looking like me.

So I will talk to you in short sentences so you won’t notice that our voices are similar. What I should tell you is Ariel from The Tempest is my favorite fictional character and that you’re sketching a likeness of him on your watermarked paper. But isn’t there always a way to turn it back around with how I say things? Ariel fancies freedom while you have four walls. He has multiple tasks to do while your main task is to eat. Still, both of you moved at night, Ariel following the orders of Prospero, you sneaking snacks. You were by yourself, slim in the dark. I awoke to find half empty ice cream cartons and missing slices of cheese. I missed you by seven hours. That’s too big a window of time.

“Do you want me to go?” I ask.

“Do what you want,” you reply.

You rub your nose with your pen. I usually stay until a nurse comes by to walk with you to dinner. She praises the vegetables and meat dishes you’ll be ingesting. You often give me a shrug and shake your head. You’re sick of small talk, especially with me.

Rather than speak, you fainted on the volleyball court. I picked up the phone, left my copier running, and drove to the hospital with the most dreadful dreams you could have about a daughter. After all, I’ve seen Lear clasp his Cordelia and bemoan his inability to understand. You were rushed to the emergency room, where they unfairly keep parents behind curtains, like anxious fans in the front who wait after cliffhangers.

The doctor told us your heart stopped for a minute and your coach revived you. How can the heart of a seventeen year old stop, yelled your father. She told me she ate too little and it was never enough, he answered briskly. He recommended treatment centers that had similar names to spas. I let your father talk, because he’s good at that. I merely sat by your hospital bed. While I fluffed your pillow, you breathed and fumbled for my hand. Both our hands had chipped off nail polish and carefully tended cuticles.

“I think I lost the game for my team,” you said. “Wish you were there.”

“I’ll be there every other time,” I said.

Today, I want it to be that easy. I’ll relish the day when you relax and let things roll off your mind, when I let things roll off my tongue. I don’t want you to aim for awe because I am awestruck by the fact that you aren’t in awe of yourself already. Maybe we can aim to get past this awkwardness, just once.

“I’ll stay,” I say. “Though, I don’t have much to talk about.”

“Mom, you don’t have to talk,” you say. “You can just be here.”

I bend to kiss you on the side of your brow. You drop your pen and accept it.

© 2010 Monique Hayes

Monique Hayes is an MFA graduate of the University of Maryland College Park, where she taught fiction and rhetoric courses. Her work has appeared in Prick of the Spindle, The Smoking Poet, Prima Storia, Birmingham Arts Journal, and Children, Churches, and Daddies.

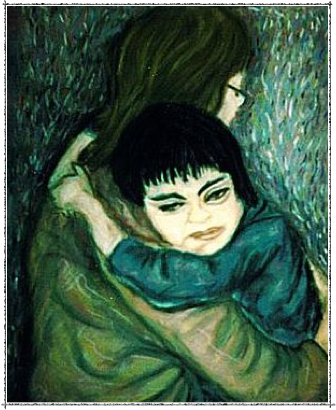

Occupation Madre © 2002 Stephen Mead resides with the artist; pastel, from the series “Heroines Unlikely.”

Stephen Mead is a published artist, writer and maker of short collage-films living in NY. His latest Amazon.com release, Our Book of Common Faith, is an exploration of world cultures/religions in hopes of finding what bonds humanity as opposed to divides.

Copyright © 2010

Touch: The Journal of Healing

All rights reserved.